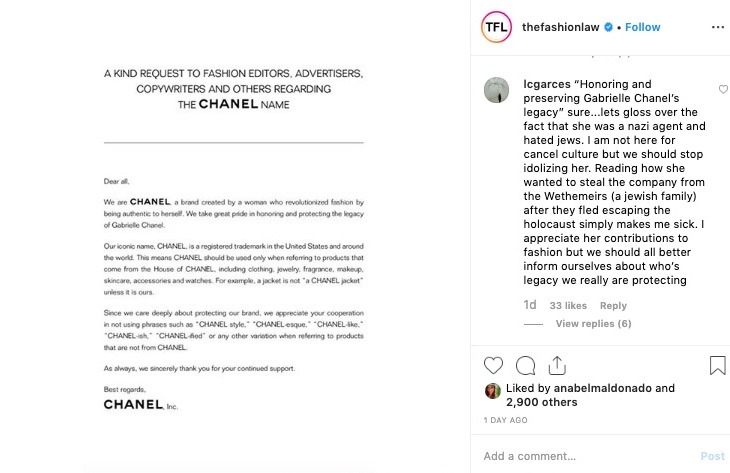

Last week, an ad periodically placed by Chanel in fashion trade publication Women's Wear Daily, reappeared, asking industry insiders, including “fashion editors, advertisers, copywriters and others”, to stop using its name to describe non-Chanel items.

It seemed like a parody at first when it began floating around fashion social media (an industry insider sent it to us with “they need to chill”), or perhaps a type of throwback, but alas, it’s an authentic and current plea from the brand, whom is apparently afraid of “genericide”. According to Julie Zerbo, lawyer and founder of The Fashion Law, genericide “is the legal term that describes a scenario in which a trademark is used as a verb (a la Google and Uber) or to identify/describe other companies’ products or services, and thus, gives rise to a risk that the mark will no longer identify the output of a single company, which is precisely what makes a trademark ... well, a trademark”, as she wrote on her Instagram.

The responses have not been kind. Replying to the post, user @loljon remarked on a decrease in quality and a direction towards narrower consumer groups: “…from switching a majority of their hardware from gold plated to "gold toned" but still keeping astronomical price points, nowadays their only last hope of surviving after Karl Lagerfeld is the colonial mentality of its Asia-Pacific market & that oil money.” Others responded to the mention of Gabrielle Chanel’s legacy by highlighting her alleged Nazi ties.

Source: instagram.com/thefashionlaw

Psychologically speaking, the ad reads more like a strategic defence mechanism against potential irrelevancy and dwindling appeal. Is the genuine concern really that fashion journalists are using Chanel as a descriptor instead of merely accurately stating the name of a well-known textile, IE “tweed”? Or is this a thinly veiled attempt at asserting themselves as number one?

ironically, experts say that becoming so generic that your brand name is used as a verb or to describe an aesthetic can only be a good thing, which Zerbo outlined here, quoting now-Harvard Law professor Rebecca Tushnet who told the Times in 2009, “The risk of [a trademark] becoming generic is so low, and the benefits of being on the top of someone’s mind are so high,” the latter being especially true in the ever-crowded consumer marketplace.”

The definition of “crying wolf” means to send a false alarm for danger, and correspondingly, there doesn’t seem to be a genuine need for this paid placed warning. Moreover, considering the brand’s ubiquity, staid design and marketing strategy, which really hasn’t changed much in decades, who’s leading the genericization?

Why the American fashion capital and its millennial consumer seem to be obsessed with nostalgia, how The Row outdid itself again, and the controversial element in Raf Simons’s looks…